Keith Burgun is an independent game designer, author and blogger. In this guest post for AC&A, Keith explains how Threes, a simple, abstract premium game, has achieved success via word of mouth.

Premium games live or die on their ability to create a strong word of mouth. Today I will be discussing Sirvo LLC’s game Threes, available on the App Store for $1.99, and the many methods it has been able to use to compel players to tell their friends about this game. The game is designed by Asher Vollmer.

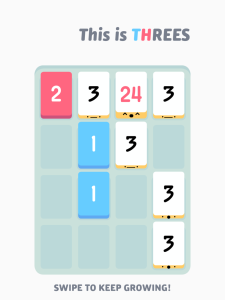

Threes is an abstract tile-moving / matching game. Like many abstract tile moving games, such as Candy Crush Saga, Dungeon Raid or Bejeweled, it involves arranging tiles around on a grid to create combinations that yield points. Unlike many abstract tile-moving games, however, the player cannot individually manipulate, rotate, or insert shapes as you please. In this game, the player manipulates the grid by sliding the entire grid of tiles up, down, left or right to create combinations.

Tiles contain numbers – multiples of 3, such as 3, 6, 9, 12 – and by shoving identical tiles together against the walls, they double and become a larger multiple. So shoving a 12 against another 12 causes it to become a 24, and so on. As the player shifts the board, a new tile is brought in, with a “Next Box” (a la Tetris) giving you a general idea of what kind of tile might be coming next.

One is reminded of Spry Fox’ hit abstract game Triple Town. Triple Town’s games can last sometimes hours, however, which is arguably a longer play session than this kind of gameplay can support, and certainly too long for a mobile game. This game has all the strengths of Triple Town, but in a tighter, leaner package, with a deeper core mechanism.

The game ends when the board fills up and no more moves are possible. At this point, the player’s score is calculated, with larger numbers being exponentially more valuable than smaller numbers.

Unintimidating Presentation

An important part of the very first experience a player gets with Threes is the presentation. It combines a spartan white abstract look with a rounded, friendly, cartoony personality. Small details like original-looking fonts, a pleasing, subtle color palette and somewhat After-Effects-looking moving text give the player the feeling that this is a quality product that someone – someone with serious graphic design ability – really cared about this thing.

The presentation, while sleek, also comes off as sincere – it is presented as a thing which the authors probably actually liked themselves. This is striking and attention-getting against a backdrop of thousands of iOS games that come off as cynical, or rushed. Such a presentation goes a long way in creating a feeling of both intrigue in players, as well as good will towards the developer.

It also does a good job of looking serious, as in looking like something an adult would want to interact with, while still looking fun. It straddles the line nicely, and does something that a lot of abstract games fail to do: invite, rather than intimidate the player.

The game takes simple rectangular tiles, and gives them personality in three ways. First, it puts a small, abstract, cute face on the sides of each tile. Further, the tiles actually have very short, non-annoying voice-acting that happens. Tiles will say, “Sup!” or “Hello!” when formed, accompanied by small animations on the faces. Finally, the game will, the first time you play, have small popup text that tells you a sentence or two of flavor text about the different numbers. Injecting a cute and charming theme into what would otherwise be a dry-looking abstract was both a great idea and well-executed. The overall visual look is similar to that of the popular iOS word-game Letterpress, but unlike that game, Threes has a distinct personality.

The developers also worked hard to present their game as a sincere, non-cynical product. They added to this by not only making the credits (three developers, by the way) extremely accessible, with their names and Twitter handles visible from one of the main menu screens.

Gradual Engagement

Threes title screen allows you to “play around with” the basic mechanisms of Threes like a toy. There are a set of five or six un-matchable (each tile is unique) blocks and the player can move them around, just for fun. This also compels the player, in that there is a certain visceral pleasure in simply moving these blocks, and it suggests that learning to play this game will be easy.

Threes title screen

Indeed, learning this game is easy, and it’s made totally painless with a simple, short tutorial that the player is forced to play on his first play. The tutorial leads the player simply, clearly, and perhaps most importantly, quickly through the game’s few rules, after which the tutorial seamlessly transitions into a real game.

The seamless transition from tutorial into actual game again fortifies a feeling that this game actually is “easy to learn, difficult to master”. It does not transition into any kind of safe or easy mode – it transitions into the actual game. Unlike a long, drawn-out tutorial which can make the player feel like they’re being treated like a child, Threes makes the player feel like they are being trusted; that they are adults.

As the player continues to play, hints and strategy advice sometimes pops up. It’s a very natural way to help the player learn – somewhat like having a friend watch you play and giving you a few pointers.

Building a Discipline

We often use the term “puzzle game” for these kinds of games, which I think can be misleading, especially for a deep game like this. Puzzles are generally somewhat shallow and disposable things. When we play them, we solve them, and then that individual puzzle no longer has any use to us.

Abstracts such as Threes, I do not consider puzzles, because they are not about pursuing solution. Much more like playing chess or tennis, Threes is a game about building a discipline. Despite the fact that it is such an easy game to learn to play, the depth of this gameplay system is quite high. Players have already begun developing strategy guides for the game.

Abstracts such as Threes, I do not consider puzzles, because they are not about pursuing solution. Much more like playing chess or tennis, Threes is a game about building a discipline. Despite the fact that it is such an easy game to learn to play, the depth of this gameplay system is quite high. Players have already begun developing strategy guides for the game.

Threes takes advantage of its considerable depth and replayability by incorporating the iOS Gamecenter “challenges” feature more directly and clearly than many other games of its kind. When the player gets a high score, it’s easy to challenge a friend to getting something higher. In fact, several gameplay metrics can be used as challenges.

This social aspect, while light, is just enough to facilitate players competition with each other. This, in turn, helps to become a source for word of mouth. Players post their best scores on Facebook and Twitter, and others post themselves beating those scores. Meanwhile, many current non-players look on as they see this happening in public. The Twitter integration in particular is fantastic: because of the simple layout of the board, players can post the end-state in a Twitter picture and it’s easy for everyone to see what happened.

Conclusion

In many ways, Threes has a lot of qualities that should make some development teams very concerned. It’s abstract, it’s a high skill game, it’s deep and difficult to master, and it’s not freemium. These are all qualities that I think many developers would shy away from, in a time when we generally think of heavily themed, low skill games as being the most profitable. However, because of the sincere, lighthearted approach, clean and elegant tutorial, and most of all, trusting the audience, Threes is a game with fantastic word-of-mouth power.