[Editor’s Note: Contributing writer Simon Newstead is CEO and Co-Founder of Frenzoo, a 3D Fashion startup and the writer of the VR Fashion blog. He can be contacted at: simon at frenzoo dot com.]

Much has been written on why Google pulled the plug on Lively, its 5 month old virtual world.

The consensus, as Google themselves explained, was a need to “focus more on our core search, ads and apps business”.

Most observers viewed the cancellation as a tough but correct decision during a major slowdown in its core online advertising market. Many questioned the launch of the service in the first place. A search company moving into 3D cartoon chat and online gaming without a clear business model seemed a bit of a stretch.

Even Lively engineering manager Niniane Wang admitted at Virtual Worlds London last month there was still no internal decision on Lively’s virtual economy model – not a great sign for a public service several months after launch.

However there were other factors that also helped contribute to the demise of the Lively service. These may not have grabbed as many headlines, but they had an impact, and not in a good way:

1. Rarity (or lack thereof)

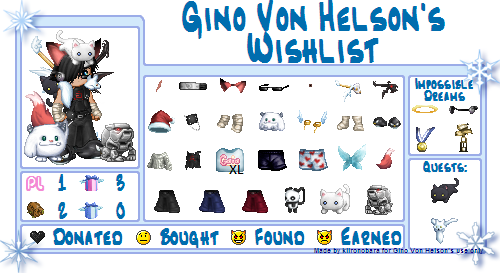

Why do World of Warcraft players grind for hours and hours on end to level up or gain a new weapon or skill? Why do millions of Stardoll fans log in every day just to get their daily StarDollar allowance? Why do Gaia Online users save for months (or plead total strangers) to buy that one special item at the top of their wishlist?

Rarity.

The cardinal rule: make items rare. I.e. require effort and/or money to acquire items, and those items become highly sought after. Desire breeds addiction, addiction plus good, fun gameplay = many repeat visitors.

Yet the day Lively opened its doors, all items in their catalog were free. With that precedent set, nothing “felt” valuable. With that, there was no “desire” factor or goal to strive for – and far less motivation to keep coming back.

This design decision made Lively feel like a “throw away” environment, and users responded in turn.

2. Too powerful and complex an interface

As Ars Technica observed in its launch review, the user interface was difficult.

Unlike Second Life, Lively was designed to be a casual “pick up and go” experience for the mainstream – yet the UI wasn’t designed that way.

For example, many users (myself included) didn’t know how to make our avatars walk around a room.

Frustrated right clicking, left clicking, and hitting arrow keys yielded nothing. It turned out that the way to walk was to hover the mouse over your avatar, then drag and move the mouse to cause your avatar to walk around. Not intuitive.

You might think that the way to solve that was to use a more standard control, for example left click on a place and avatar walks towards it. However this brings up a higher order question: Why was walking even allowed in the first place?

Walking didn’t add anything to the social chat experience except complexity and confusion.

Lively’s competitor and 3D chat leader IMVU recognized this fact and even years after their launch, IMVU doesn’t support avatar walking.

Why?

It doesn’t need to.

3. Too rough, too early

Unlike an unknown startup, anything Google launches to the public is going to attract a day one audience of millions.

That’s what happens when you are the most visited web company in the world. You had better make sure that it’s ready. In Lively’s case, it wasn’t just the lack of Mac support that caused fits among its early user base (although that didn’t help).

It was other issues such as lack of an open content program, leading to a dearth of selections in the store on the first day. A few months would have made all the difference as Google had truly promising and unique content ecosystem in development which could have been a game changer.

It was also many little things:

Anger and confusion greeted a friend who had spent an hour decorating her room, yet returned a few hours later to find strangers had put sofas on the ceiling, tipped over chairs and rearranged plants into a jumbled mess.

All because at launch it was too easy to unknowingly allow others to edit your public room. This and many other small, yet very frustrating user experience issues surely would have been cleaned up with more time in a closed beta.

First impressions count even more in a spotlight.

4. Audience and art

Lively tried to be everything to everyone right from day 1.

Unlike other games based around a theme – be it anime lifestyle in Gaia Online, music in vSide or 3D Avatar Fashion in Frenzoo (disclosure: this is my product) – Google went for an audience of everyone. Or, as Google put it themselves, “Be who you want to be on the web pages you visit.”

This was always going to be an ambitious goal, but it was very difficult to create a cohesive experience with a mix of radically different art styles for the avatars.

In successful services such with Nintendo Mii or Habbo Hotel, there can be plenty of diversity in look but yet a single unmistakable avatar style glues the whole experience together.

However in Lively, you had tiny bears hugging tall skinny cartoon girls, while pigs walked around in circles.

The goal – total freedom of art style – may have been worthy, but put them all together in a chaotic 3D chat environment and the net effect was chaotic and off-putting for users.

5. No profile to call home

It’s an irony that a service that pushed the outer limits of web technology, the most basic social web features such as a profile page, were conspicuously absent.

Nearly every successful online game or web community has a profile page or home screen, as the center of the social experience and to build your own virtual identity – be it for role playing or just making friends.

IMVU’s profile pages are buzzing with user expression and customization, MySpace and Facebook have built their social businesses entirely around profile pages. Yet surprisingly, Lively, which billed itself as the next step in the “social web,” didn’t support web profile pages at launch.

Conclusion

Does the demise of Lively spell the deathknell for virtual worlds?

I don’t believe so. Whilst there has been some excess in hype in parts of the industry, for many players abundant opportunity is still there. The rapid growth of other virtual worlds from IMVU through to Buddypoke and Stardoll and growing revenues seem to bear that out. Not to mention the massive growth in MMO revenues in the past three years.

However in Lively’s case, Google made several big and small mistakes. Combined with a confused business model and no long-term commitment from the Google mothership, this ultimately doomed the otherwise promising service to brief and inglorious lifespan.

The problems could have been fixed and focus found for Lively. IMVU’s first year was plagued with bugs and issues; but as Silicon Alley Insider put it succinctly, in Google’s case they didn’t even try.