[Editor’s Note: Before embarking on his own startup, contributing writer Adam Martin was CTO at NCsoft Europe. Adam is a voracious gamer with a professional background split between programming and business. He blogs at T-Machine and can be reached at adam.m.s.martin at googlemail.com]

At FreeToPlay.biz, we’ve spent a lot of time examining how free-to-play (F2P) games work: their advantages, challenges, demographic appeal, etc. But we haven’t yet looked as closely at who makes these games what they are and who shapes the future of the F2P sector: the Publishers.

In the online games industry, there are three separate categories:

- Who makes the games? (the “Developers”)

- Who funds and markets the games? (the “Publishers”)

- Who supplies the games to the users? (the “Operators”)

Historically, the core games industry (i.e. retail) has had just two categories: Developers and Publishers. With the advent of online games, a major offshoot of Publishers has appeared: Operators, who take none of the up-front risk of a traditional Publisher and focus instead on capitalizing on the game once it’s made (usually by taking it to territories and languages that the original publisher cannot reach).

This article looks at the Publishers: the businesses that take the bulk of the risk by financing the game. If a game is fully developed, and launched, but fails to earn out, the Developer makes no profit but no loss; the publisher, on the other hand, makes a net loss of whatever the development cost was, minus the game’s revenue.

Operators don’t usually enter the picture until the game has already gone to market in at least one territory, and set an expected level of popularity / revenue, so they have the lowest risk of all. Ultimately, the Publishers have the greatest control over what future games get developed.

For each Publisher, we start with their Name, Country, Incorporation year, and 2008 revenues (as estimated by the company in their latest financial report, or as estimated by me based on similar companies and markets).

1. Nexon, South Korea, 1994, $300m (est)

Nexon is probably the most famous of the F2P publishers, thanks to two hugely successful games – MapleStory (2003) and KartRider (2004) – which have both attracted many tens of millions of players. Although MapleStory came first and has been the bigger global success with over 100 million players internationally, KartRider did much better in its home market of South Korea. Some reports allege KartRider has been played at one time or another by more than a third of the population of the country.

But it’s not just about sheer number of players. Nexon has also consistently made a huge amount of money out of their virtual item sales revenue model, with quoted revenues of $230m revenue for 2005, most of it coming from F2P offerings. Unfortunately, the Korean head office has been uncharacteristically quiet (for a Korean company) for the last few years, with the only good data coming from Nexon Publishing North America, a subsidiary with a games operations office in Los Angeles and an original game development studio in Vancouver, Canada.

Apart from pioneering the use of F2P, it’s worth noting that Nexon was also a pioneer of subscription-based online games. They developed one of the first ever MMOs in Asia – The Kingdom of the Winds (1996) (subs). One of the lead programmers, Jake Song, left to be part of a newly-founded company – NCsoft – and develop their first MMO, Lineage (1998). NCsoft is now one of Nexon’s major competitors. Lineage for many years held the world record for largest number of players for any MMO, and NCsoft is still an almost entirely subscription-based MMO publisher.

2. Giant Interactive, China, 2004, $240m (est)

Giant Interactive is currently the top Chinese F2P publisher by revenue, although if NetEase’s rumoured conversion from subs to F2P for their main games goes ahead, Giant could slip down to a close second. Giant was founded by Shi Yuzhu, who made a fortune from selling diet-supplement pills… and then lost it all when the original Giant Group went bankrupt in 1997. He made a personal comeback with a new company based on similar pills, Nao Baijin (“Brain Platinum”) – and an exceptionally aggressive and intensive marketing campaign – then went on to found Giant Interactive in 2004.

Which all helps to explain Giant’s leading game, ZT Online (2006), which with around 10 million players and an ARPU of over $40 a month generates the bulk of their revenue. That ARPU figure stands out for being around 50% higher than most other operators.

Shi’s Nao Baijin pills were helped to huge sales through a massive nationwide marketing and sales team, and for Giant he went a similar route, using a thousands-strong sales team to personally visit the Internet Cafe’s around China and promote the game. This contrasts with the other online game publishers and operators, who – like their Western counterparts – generally do their marketing through much cheaper means, such as online advertising and industry events like conferences. According to the company’s website, they now have over 3,000 sales and marketing people. It seems fair to say that this is a marketing-lead business, and that we can expect to see Giant consistently getting every ounce of revenue out of its games over the coming years.

The creation of an alternative, Pay-to-Play (PTP) version of ZT may be an example of this. ZT Online PTP (2008) comes with a $2 / month flat subscription, or $0.01 an hour, and no item-purchasing allowed. Where operators and publishers go for parallel monetization, its nearly always the other way around: making available an F2P version of an existing subs game. Indeed, NetEase appears to be doing that right now with their major titles, in an attempt to shore-up the losses in players they’ve seen, with many of them allegedly moving to ZT.

3. Perfect World, China, 2004, $200m (est)

Perfect World (which is the name of both the company and their first MMO) is a Chinese MMO company that has developed and launched seven games in four years. Like all the Chinese MMO publishers, they are young, and yet have seen huge revenues on the back of massive player numbers and rapid, consistent, growth.

Interestingly, their first MMO was a traditional RPG using the subscriptions model, but for the sequel, Perfect World II (2006), they decided to switch to an item-sales F2P model.

Although (like many of the Chinese publishers) largely unknown in the Western world, they established a USA subsidiary in April 2008, and so that may well change fairly rapidly.

For 2008 Q2, their ARPU for paying customers is a decent but not unusual $27 per month.

4. Disney, USA, 1994, $1000m (entire online division)

Disney is the largest of the US companies making major use of F2P at the moment. Like Nexon, their earliest forays into online gaming were subscription based, with the likes of ToonTown Online (2003), which was also one of the first virtual worlds aimed at children, and peaked at over 1 million subscribers. They later acquired Club Penguin (2005), one of the biggest Western F2P games, acquiring approximately 10 million new users. Outside of children’s MMOs they’ve been less successful, and although they’ve used F2P in major MMO titles such as Pirates of the Caribbean Online (2007), it’s not been so well received, with numerous accusations that the F2P element was too heavily crippled.

TTO pioneered child-safe worlds, with features such as SpeedChat to protect children from other players, whose identity can never be confirmed. To those afraid that F2P worlds allow for “anyone” to play, without any way to identify them, it’s worth noting that the subs-only TTO had the same problem, and never completely avoided it. Interestingly, in 2007 Disney switched TTO to F2P.

5. CJ Internet, South Korea, 2000, $180m

CJ Internet has around 23 million people playing games at its NetMarble games portal. CJ Corporation (which acquired Plenus/NetMarble in 2004 and renamed it to CJ Internet), was originally a sugar-producing subsidiary of Samsung, and so the CJ stands for Cheil Jedang (lit “first sugar”). This may sound strange, but is a classic example of South Korean Chaebol (family-owned, government assisted, major corporations with ownership of businesses across a very wide spectrum of unassociated industries).

Their best-known game is probably Sudden Attack (2005), a clone of the hugely successful Counter-Strike (2000). Interestingly, CS’s owner, Valve Software, has commissioned Nexon to develop an “official” F2P version of CS for the Korean market, named Counter -Strike Online, due out in 2008.

Elsewhere, CJI appears to have taken a leaf out of EA Sports’ book by licensing the MLB (Major League Baseball) club names, logos, and famous players for use in their MaguMagu online Baseball game.

6. Gameforge, Germany, 2003, $100m (guess)

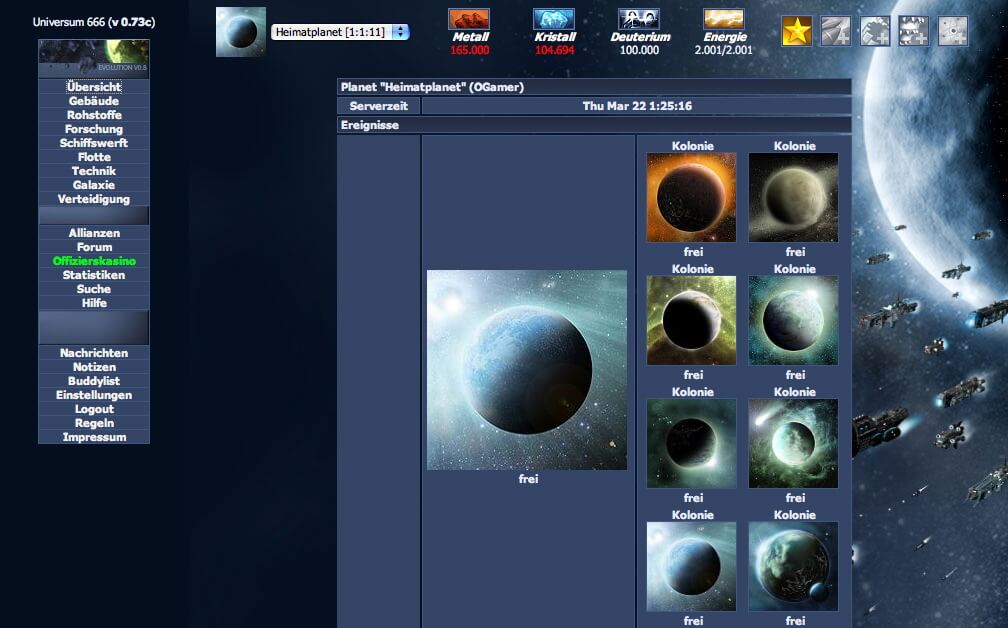

With 60 million users, Gameforge is one of the biggest Western F2P publishers. Although they have never released revenue figures, their quoted 11 million “active” players suggest an annual revenue figure somewhere in the region of $75m – $150m. Given that their games tend to be light browser-based games, I’m guessing they’re at the lower end of the spectrum.

They started off only running their in-house developed browser-based games, with the biggest (around 2.5 million players) being OGame (2002), but in the last few years they’ve branched out, and now operate several client-based games imported from Asia. One of those, Metin 2 (2007?), was originally launched as a subs game in Germany, and then switched to F2P for the localized versions launched throughout Europe. As a private company, figures are hard to get hold of, but they have quoted an ARPU of $26 for the 1.1 million M2 players in Europe (although its not completely clear if that includes the German subscribers).

Gameforge is particularly interesting because by focussing on rapid, high-quality localization of games to different languages (they claim to have localized into 25 distinct languages already) they’ve successfully moved from simple game developer to a major importer/operator of South Korean games. This is almost the opposite of Acclaim, but they’ve done it more slowly and until last year self-funded, so they appear to be taking the slower, harder, but more defensible and lucrative approach.

![]()

7. HanbitSoft, South Korea, 1999, $65m

HanbitSoft came to fame in 1999 for being the South Korean distributor of Blizzard’s multiplayer (but non-MMO) StarCraft (1998), a best-selling game in USA/Europe, and one of the biggest-selling games ever in South Korea. SC was monetized as boxed retail sales only, with no ongoing revenue stream, and in South Korea became (and still is) a major competitive sport, with two TV channels running their own live SC leagues.

However, right now HanbitSoft is probably best known outside Asia for being the main publisher of the failed Hellgate:London game from the now-defunct, ex-Blizzard-led, Flagship Studios. They’re one of the few companies in this list to have made a substantial net loss on funding games, and it’s interesting that this happened with a game that most closely bridged the game between “traditional mainstream Western action game” and “F2P MMO”. Hellgate had a troubled development and probably failed for many reasons, but one of the frequently cited complaints was that the monetization model was neither F2P nor subscription, but a mix of the two. This appears to have fared poorly.

In May 2008, T3 Entertainment, best known as the developers of Audition Online (published by Yedang Online), became the largest shareholder in Hanbitsoft. This may be T3’s first move into being a major publisher in their own right.

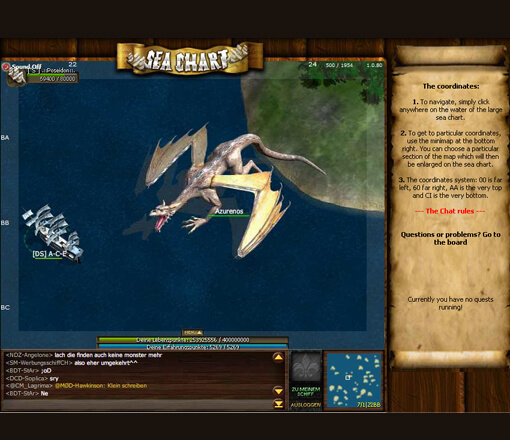

8. Bigpoint, Germany, 2002, $25m (est)

Bigpoint has been through two name-changes, starting out as “m.wire”, a self-publishing developer of browser-based sports games such as IceFighter (2003) and Soccer Manager (2004). In 2005 they underwent a change of name to better reflect this specialization, becoming “e-sport”, before switching the company name to match their gaming portal – bigpoint.com – in 2007. Their portfolio now is diversified away from sports games.

Bigpoint may appear at first glance to be nothing more than a smaller version of Gameforge (see above), with around one third of the annual revenues, and half the number of players, and a narrower portfolio (unlike GF, BP hasn’t started to operate any Asian games, nor branched out into client-based online games). That changed earlier this year when the 3 main VCs (all low-end investors) exited in a buyout split between the CEO, another VC fund, and … NBC Universal, selling 70% of the company for $110 million. The link with NBCU has already started to show, with their SCI FI channel website now carrying two item-based F2P games from Bigpoint (although not exclusively). This buyout made clear the company’s intentions: they swapped a group of small European funds for a 35% stake from a mainstream USA-based entertainment giant (more than $15b a year in revenue).

Bigpoint may appear at first glance to be nothing more than a smaller version of Gameforge (see above), with around one third of the annual revenues, and half the number of players, and a narrower portfolio (unlike GF, BP hasn’t started to operate any Asian games, nor branched out into client-based online games). That changed earlier this year when the 3 main VCs (all low-end investors) exited in a buyout split between the CEO, another VC fund, and … NBC Universal, selling 70% of the company for $110 million. The link with NBCU has already started to show, with their SCI FI channel website now carrying two item-based F2P games from Bigpoint (although not exclusively). This buyout made clear the company’s intentions: they swapped a group of small European funds for a 35% stake from a mainstream USA-based entertainment giant (more than $15b a year in revenue).

There are also signs that they may be one of the first wave of companies to get F2P games on PlayStation 3. To date, all games distributed via the PSN store have been allowed free demos but with extremely limited functionality. Now, along with demoing one of their games running on a PS3, Bigpoint’s CEO has stated that their games will be available on console “with free registration as usual, and ready to play right after download”.

That gives Bigpoint two major relatively untapped markets for their style of F2P, and with their powerful media partner, they may yet leapfrog Gameforge and secure a large chunk of one or both of those markets.

9. Frogster, Germany, 2005, ? (Frogster’s IR website is offline)

Over the past ten years there’s been a clear trend for the young, fast-grown, cash-rich South Korean online game companies to look for their next round of growth in the West, and so establish subsidiaries in Europe and the USA, starting with NCsoft’s acquisition of Destination Games in 2001. Frogster is one of the first companies to actively reverse that trend by taking wealth generated in Europe and the USA, and establishing a subsidiary in South Korea. This subsidiary is managed by a previous General Manager of Gravity, a Japanese online games publisher (non-F2P).

Originally formed as a management buyout of a standard middle-tier PC games publisher, Frogster has been focussing on repurposing as a pure MMO publisher / operator, and spun off it’s conventional PC games division in 2007. Like a couple of operators and publishers, they’ve been switching or parallelizing their subscription games over to F2P, e.g. in 2008 they added an F2P server to Bounty Bay Online (2006).

10. Zynga, USA, 2008, ? and Social Gaming Network, USA, 2008, ?

For the final entry, we’re going with something a bit different: not one company, but two, and not based on revenues, but on market and consumer base. And both companies are less than a year old. There’s a reason for this: unique in the F2P world, they’ve both risen to fame (and around 50 million users each) on the back of other people’s hosting platforms in the guise of Social Networking sites, especially Facebook. They’re included as a pair because, to be honest, there’s so little to distinguish between them.

They represent a second wave of disruptive F2P businesses, thanks to that tie-in with the major Social Networks; without any partnership deal, in less than a year they’ve achieved user figures – as high as 18 million active – that are a notch faster again than the super-fast-growing Chinese F2P publishers. We’re seeing them uncharacteristically early – it took the games industry a good 5 years to even notice the existence of games like Runescape (now running at well over 1 million subscribers). So it’s no surprise that things like revenue levels are unquoted and relatively meaningless for these two – those will become established over the coming year or so. What we’re looking at here is very early businesses whose only direct, clear, measurable value (and indicator of probable lasting success) is the huge audience they command. These are almost typical web businesses, not games businesses, but the expectation among many is that with hindsight we’ll look back and say that they were the start of the new combined web + games industry, which is widely expected to eclipse traditional games.

Of course, they could easily sputter and fail (although it’s quite hard not to be profitable when you’ve got tens of millions of users), so they’re here at number 10.

Notes on inclusion

Direct revenue comparisons are difficult

Approximately 1/3 of publishers don’t publish their revenues, and another 1/3 don’t separate out their F2P revenues from their other revenue. The most accurate known figures are quoted for each company, sometimes these are F2P revenue, other times it’s an aggregate including non-F2P and even non-games revenue.

Many Operators think of themselves as Publishers

There are different definitions of “Publisher”, and the line between the two is often blurred. I’ve tried to include only companies who are are substantial publishers by the risk definition given above, but some publishers may have been accidentally categorized as operators. A followup article will look at the companies who are primarily Operators.

Companies have to be mostly F2P

Several major companies with large revenues have been excluded because the vast majority of their online-game revenue comes from subscriptions. Only companies that gain the bulk of their revenue from F2P, or have made major switches from subs to F2P, are included here.